Aino Kajaniemi (born 1953) lives with her family in the beautiful central lake district of Finland. It is the house that she grew up in, and her studio is in the cellar. The rhythms of nature and everyday life influence her work. Her images of female protagonists, shown in the midst of thought or caught in interior monologues, are as assured as the line drawings of women made by modernist painter, Henri Matisse.

Aino Kajaniemi (born 1953) lives with her family in the beautiful central lake district of Finland. It is the house that she grew up in, and her studio is in the cellar. The rhythms of nature and everyday life influence her work. Her images of female protagonists, shown in the midst of thought or caught in interior monologues, are as assured as the line drawings of women made by modernist painter, Henri Matisse.“The subjects of my work usually originate from the innermost heart of a human being; sorrow, joy, uncertainty, guilt, tenderness, memories, and so forth.”

The eyes of her subjects look down, off to the side, or into themselves. This invites the viewer to consider beyond the picture and build a narrative that passes through and between the woman in the tapestry and the interiority of the viewer. Kajaniemi’s subjects are not passive women offering themselves up to be gazed upon, they are intently involved with their inner lives and this self involvement inspires a similar participation within the viewer. Kajaniemi usually produces eight to ten small tapestries that are displayed together in order to give multiple perspectives.

The eyes of her subjects look down, off to the side, or into themselves. This invites the viewer to consider beyond the picture and build a narrative that passes through and between the woman in the tapestry and the interiority of the viewer. Kajaniemi’s subjects are not passive women offering themselves up to be gazed upon, they are intently involved with their inner lives and this self involvement inspires a similar participation within the viewer. Kajaniemi usually produces eight to ten small tapestries that are displayed together in order to give multiple perspectives.  She uses the difficult and labour intensive technique of tapestry weaving. She selects which aspects of her narrative will be hidden and which will be revealed. Yarns are interwoven and carefully considered and the process is painstaking. Craftsmanship is important to Aino Kajaniemi. Her line is controlled, yet dramatic, nervous, and spontaneous.

She uses the difficult and labour intensive technique of tapestry weaving. She selects which aspects of her narrative will be hidden and which will be revealed. Yarns are interwoven and carefully considered and the process is painstaking. Craftsmanship is important to Aino Kajaniemi. Her line is controlled, yet dramatic, nervous, and spontaneous.“My textiles are my way of thinking. I appreciate simplicity, but I work things out in a complicated way. "

Yet her work has a swift and easy look, as if it was just a sketch. To achieve this casual look, she does many pre-sketches beforehand. She may draw the same idea over and over, ensuring that the composition is interesting and that the subtle glance of the subject is emotional. Eventually she translates the sketch to the loom and uses a single line of black wool to weave her idea into white or natural backgrounds always allowing for changes that may arise.

Yet her work has a swift and easy look, as if it was just a sketch. To achieve this casual look, she does many pre-sketches beforehand. She may draw the same idea over and over, ensuring that the composition is interesting and that the subtle glance of the subject is emotional. Eventually she translates the sketch to the loom and uses a single line of black wool to weave her idea into white or natural backgrounds always allowing for changes that may arise. Her work never loses the feeling that it is just an easy sketch, made quickly when the subject was caught unaware in a reflective moment.

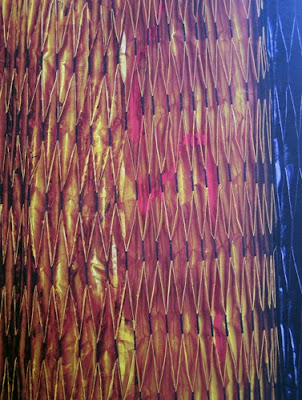

The idea of lace or lace-like pattern appears often in her work. These spaces, lines, curves and floral shapes translate a feminine, fragile sensibility and contrast with the pared down, almost tough, tapestry weave. Out of place colours and different weights of yarns are added and disrupt the even warp and weft. We remember that cloth eventually wears out after time because this work seems to hold its own destruction within itself. It appears to be something old that has been mended, and eventually, some time in the future, it will wear away.

The idea of lace or lace-like pattern appears often in her work. These spaces, lines, curves and floral shapes translate a feminine, fragile sensibility and contrast with the pared down, almost tough, tapestry weave. Out of place colours and different weights of yarns are added and disrupt the even warp and weft. We remember that cloth eventually wears out after time because this work seems to hold its own destruction within itself. It appears to be something old that has been mended, and eventually, some time in the future, it will wear away. “I get all my threads from flea markets now” she said in 2008 which explains the surprising tones and materials that enliven her new work. This up-cycling of used or surplus materials is an ethical decision. Our current material culture is ‘awash in plenty’. Kajaniemi’s pared down imagery and slow intent sings of order within the disorder of our wasteful world.

A sense of isolation is palpable in her work, relating perhaps to the loneliness of the beautiful Finnish language, unique in Europe.

A sense of isolation is palpable in her work, relating perhaps to the loneliness of the beautiful Finnish language, unique in Europe. “Weaving is finding”

After 30 years she still allows the weaving itself to make unexpected decisions and avoids complete mastery. If, as Rilke proposes, poetry’s purpose is to address the natural growth of a human’s inner life then these weavings are poems.

All images are from the artist's website.

Text is from my 2010 BFA dissertation, "The Immensity Within Ourselves" for Julia Caprara School of Textile Arts.