The quilts in this post are all from the Bosna Quilt Werkstatt , an ongoing organization of quiltmakers that began as a response and a way of caring for humanity during the upheavals of the Bosnian War.

Since 1946, Bosnia and Herzegovina had been organized into a republic as part of communist Yugoslavia. The ethnic unrest among the people who lived there exploded into such a harsh severity in 1992 that NATO become involved. It was a civil war in which the Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) were being eliminated by the Serbs. Between 1992 - 95, over 200,000 people were killed and 2 million were displaced. For a better understanding I've put a link for you here .

Women, children, and grandparents fled the atrocities and men disappeared.

The story of these quilts began in the Galina refugee hostel, in Vorarlberg, Austria on Palm Sunday, April 1993, already a year into the war.

Lucia Feinig-Giesinger, a young artist, listened to the women, and was moved to help them continue with the quilting artform they were already familiar with. Making is a form of healing.

Lucia's art training was in painting, and she was not acquainted with the techniques involved to make a quilt. However, the materiality and usefulness of the blankets, combined with the craftsmanship required to make them appealed to her. She also liked how quilts are warm yet light and she was inspired to create minimalist designs.

The women did all the construction seams as well as the beautifully dense hand quilting.

The seams were machine sewn on donated sewing machines in an adapted military garage.

The hand quilting was done on the beds in the hostel by mothers and grandmothers, the children playing nearby.

There was constant interaction of the stitchers with Lucia and with the project manager who would procure the materials and did the public relation work. Not only were the quilts therapeutic for the makers, they were sold and thus provided needed income. The quilts became famous, and have since shown around the world in quilt festivals as inspirations for community healing work as well as modern design.

The project stopped for a while in 1998, but started up again in 2004 and currently 12 women design and stitch quilts for the Bosna Quilt Workstatt.

The lead artist, Lucia Fenig-Giesinger is interviewed by Pionira at

this link.

The quilts continue. The Bosna quilts were invited to the International Quilt Festival, Houston, USA in 2020.

The

website has a catalog of newer pieces that are available for purchase. The website also lists the many places that the quilts have shown since 1998.

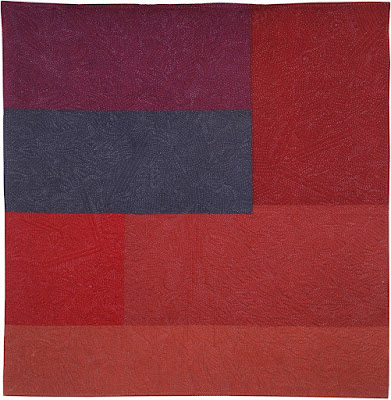

The above quilt was made in 1999. The stitcher's name is Safira Hoso. 76 x 57 inches Safira was able to return to Bosnia and Herzegovina when the war ended and continues to make quilts for the Bosna Werkstatt.

Safira’s quilt is from the book: Vernnahate Zeit: Die Bosna Quilt Werkstatt, published by OttosMuller Verlag , Salzburg in 2007. (In German, but there is a supplemental section that has an English translation). The book's text was written by Wilibald Feinig, the artist's husband. The English supplement was translated by John Christensen in 2007.

The quilt below is also stitched by Safira, and you can find it on the Bosna Quilt website catalog. It was made in 2018 and measures 70 x 55 inches.

Several websites and blogs feature these quilts.

Quilts are a feminine, dialogue-born form of art. Up to the present day quilts have been overlooked in art histories.

Art that emerges from the hardships experienced by a new European nation driven to war is an art meant to be grasped and touched. These quilts have a place not just in ruins, but also museums. Bosna Quilts are now granted a space within the broader house of art. Bosna Quilts are nomadic art.

(Willibald Feinig translated by John Christensen)