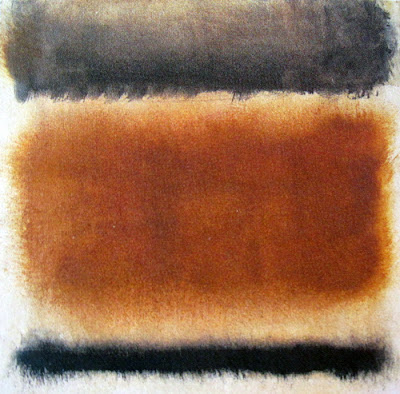

No. 12, 1951 57" x 52"

Mark Rothko's paintings from the 50's are probably the most obvious artwork to feature in this blog about the modernist aesthetic. Certainly, his work has inspired generations of artists and moved countless art lovers for seventy years. When we think of high modernism, his name is one of the first mentioned.

Around 1940, he took a year long break from painting to continue his intensive self study of philosophy and myth. His paintings at the time were figurative, but his writing of that time shows that he was honing his personal understanding of the colour field work in which he would eventually reign supreme.

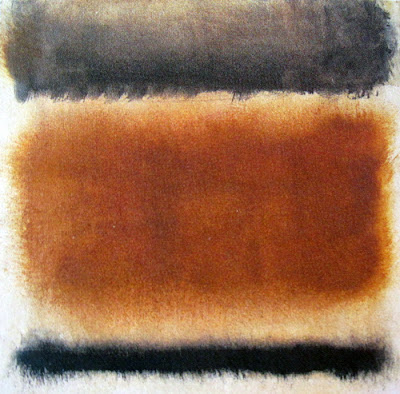

No. 8, 1952 81" x 68"

He wrote a book which remained in manuscript form for over thirty years. It was never really edited by Rothko himself, but he held onto it through a divorce and second marriage, two children, house moves, and his own phenomenal success, probably thinking that someday he would have enough time to do so. His son, Christopher Rothko, has edited his father's manuscript and writes a lengthy introduction about the difficulties of doing so.

Christopher's respect for his father's legacy is evident. "Rothko had no patience for anything that did not aspire to the highest ideals."

Yellow and Blue, 1955, 102" x 67"

In the book, it is amazing to read that Mark Rothko was searching at that time for a way to introduce the tactile sense into his painting. He feels this can be done with the use of light.

And, he wanted to have emotion in his work, identifying the tragic emotions like fear and anger as being the most important, (although artists working today have added a more positive emotion, wonder, to that list). As well, Rothko wanted to mix the subjective with the objective and come to a kind of universality.

These are the ideas of phenomenology, but Rothko never refers to

Merleau Ponty, or

Gaston Bachelard in his writing. He probably was not aware of them although they were working at the same time. (Merleau Ponty's

Phenomenology of Perception was published in 1945, Bachelard's

Poetics of Space in 1958.) For me, this makes me understand why Rothko's work has never lost its ability to move viewers to tears. He is able to connect to the immensity within (Bachelard's term) through the body's tactile senses, strong emotion, and a kind of universal intimacy.

It is tough going to find this essence of Rothko in his writing however, because his ideas are often buried in a pile of repetitive complaints. While I am glad that Christopher Rothko did not remove any of his father's words, it would be a service to the art world if someone was able to summarize the great man's book into a simply understood essay.

No. 7, 1953 91" x 55"

When Rothko was painting his most famous pieces during the 50's and 60's, he did not say very much, although he was often interviewed. His words from that time have been oft-quoted but they are so mysterious. This book makes those ideas clear.

It's as if Rothko had internalized his ideas so much, he didn't feel it was necessary to spell them out for those of us who were so eager.

Orange and Red on Red, 1957 69" x 67"

Rothko quotes or summaries from the book:

"

The painter must be likened to the philosopher rather than to the scientist. Philosophers are verbal., they use numerical logic to sort out ethics. But the artist is more concerned with human sensuality." page 22

"

Our eyes, our ears, all of our senses, are simply the indications of the existence of a veritable reality that will ultimately resolve itself to our sense of touch." page 25

In the Renaissance, there were three breakthroughs for the visual artist. Linear perspective, oil paints, and chiaroscuro. But sensuality could not be expressed with these. Light was necessary, to produce the quality of emotion. page 35

Untitled, 1955 92" x 69"

While writing this book, Rothko was reading Nietzsche who believed that the entire function of art is to produce a way to endure man's insecurity. He was also reading about primitive art, and came to his own conclusion that it was closer to the emotional.

Rothko felt that the Renaissance and all that came after it, was more about the "outer reality" of perspective, light and shadow, while in Gothic times, Egypt, or Africa, art had been more about our 'inner reality'. Rothko wanted to go back to that timeless period, and terms it

the artist's reality.

Untitled, 1958 16" x 17"

All of these images are from the 2001 Beyeler gallery monograph of Mark Rothko. The text was inspired by

The Artist's Reality: Philosphies of Art by Mark Rothko, edited by Christopher Rothko and published in 2004. There is a lot of information about Mark Rothko on the web.

Here and

here are good starts. Christopher Rothko talks about the book in

this video.